The Stress-Histamine Connection: Understanding the Hidden Effects

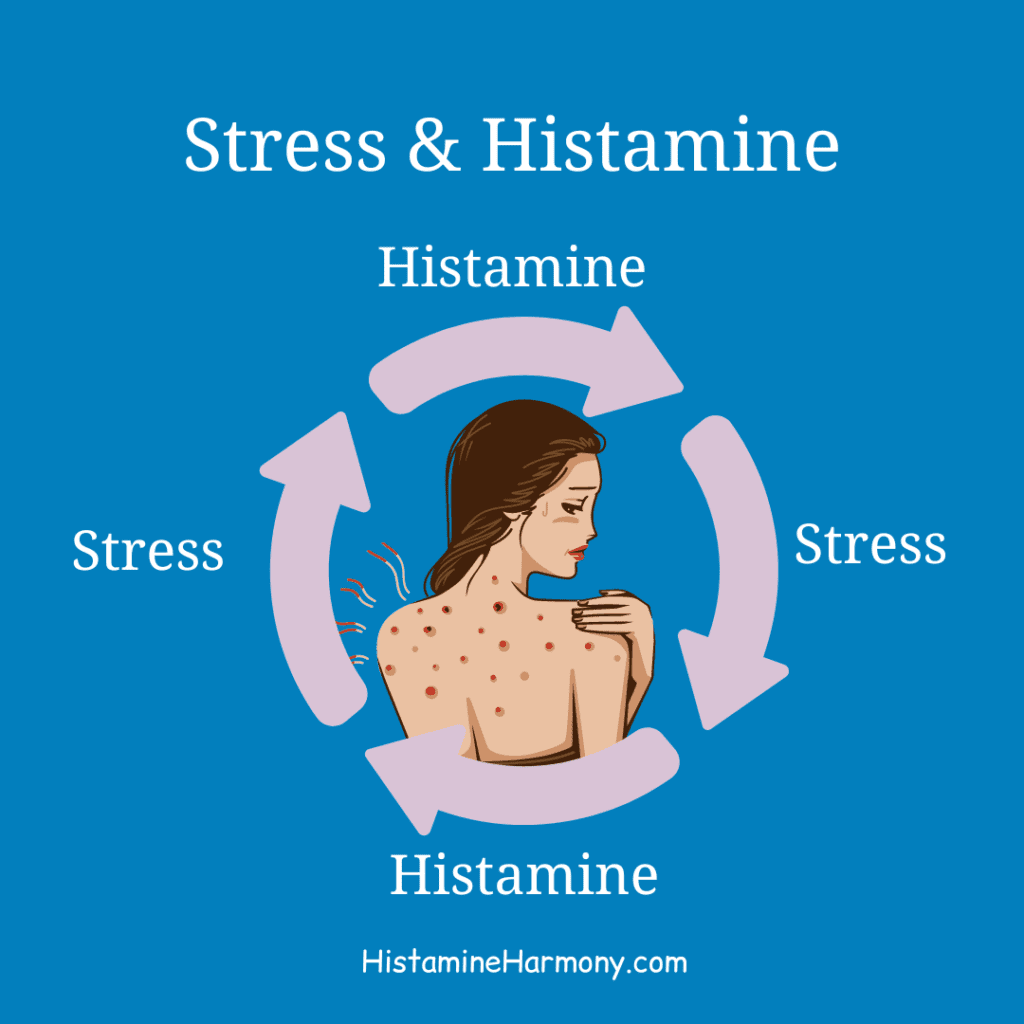

Chronic stress can wreak havoc on your well-being, disrupting sleep, eating habits, and emotional resilience. Moreover, stress plays a significant role in histamine and mast cell-related conditions.

Chronic stress can trigger the release of histamine, exacerbating symptoms of histamine intolerance and mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS). Understanding the multifaceted impact of stress is crucial for managing both your overall health and specific conditions related to histamine and mast cells.

This article goes over some of the benefits and risks of stress and the physical and mental effects it can have on our health. It also covers the biological basis behind what stress does in your body and mind.

Are There Benefits of Stress?

Before we dive into all of the negative effects of stress, let’s acknowledge that it can have some benefits. On one hand, stress can motivate you to accomplish goals, like becoming more alert and efficient so you meet deadlines. That’s especially true for short-term stress.

But too much stress over too long of a time-span has negative consequences on your mental and physical health. These can impact how well you can emotionally handle life’s curve-balls and your relationships, and can affect your eating, sleeping, and fitness patterns.

Stress can even increase your risks for short-term—or even long-term—health issues and is a known trigger for autoimmune and inflammatory conditions, including hives.

According to the Canadian Mental Health Association, stress is “our body’s response to a real or perceived threat.”

- [1] According to the National Institute of Mental Health, “stress is how the brain and body respond to any demand.”

- [2] Stress isn’t the situation (or “stressor”) itself, but rather stress is the reaction to that threat or demand. It happens when you feel threatened or when the demands on you are greater than your ability to deal with them.[1]

Stress is a reaction to a situation or “stressor”

Let’s take a second to unpack the fact that stress is the reaction to a situation or “stressor.” It’s true that not everyone has the same response to the same situation—some things that stress me out may not stress you out. For example, if you love the adventure of moving to a new home or city, it won’t stress you out as much as it would for someone who loathes packing up and meeting new neighbors. For me, especially as someone with a lot of social anxiety, moving to a new place is incredibly stressful experience.

Plus, everybody’s responses to stressors can be slightly different. Sometimes when two different people are equally stressed, one may be able to manage and recover more effectively than the other.[2] In other words, how we experience stressors can be unique, even if the biological stress response is the same.

Stressors come in all shapes and sizes, too. Some of the biggest stressors are significant life events, like changing jobs, divorce, or the death of someone you care about[1], or they can be traumatic events like a natural disaster, war, or assault.[2] Other stressors can come from day-to-day life, like parenting, dealing with a chronic illness, or being a caregiver.[1,3] Some stressors are even more temporary, like traffic on your way to work or school, or “spilled milk.”[1]

DISCLAIMER: If you are dealing with trauma or a serious mental health issue, please see a medical or mental health professional.

The most important thing to know is that stress is your body’s completely natural way of trying to protect you. There are several strategies you can use to manage it. This article goes over some of the impacts that stress can have on your life, the biological basis for it, and several uncommon ways to deal with stress.

The natural stress response

When a situation stresses you out, it’s because your body and mind are instinctively trying to help you survive that stressful threat or demand. This prioritizes the “threat” above everything else and activates your biological fight, flight, or freeze reactions.

- Fight – Stress can put your brain on “high alert,” make you feel frustrated or angry, increase your heart rate and breathing, and tense your muscles.[2]

- Flight – Stress can motivate you to run away, procrastinate, or avoid the problem altogether.

- Freeze – Stress can make you feel overwhelmed and unable to focus or concentrate on anything—including a solution to the stressor.

However, when you really think about it, many of the stressful situations that activate these natural survival mechanisms don’t actually threaten your survival. Of course, there are exceptions—reacting to a natural disaster, war, or assault may very well be for survival. The problem is that your body reacts in the same way when you’re facing a less threatening, but equally stressful situation like a job change, short deadline, parenting issues, or a traffic jam.

In these cases, your natural biological reaction may be a bit too intense for the reality of the situation—and it’s not your fault! There are biological mechanisms in place that I’ll share with you in Part 2.

Fighting, fleeing, or freezing is often not a useful strategy to deal with “every day” demands that most certainly are stressful but don’t in fact threaten your survival. But biologically, your natural reactions don’t distinguish between the two.

The 2 types of stress (acute and chronic)

Acute stress is usually very high but very short-lived. An example might be swerving to avoid a collision. In this case, the mind goes into “high alert” stress mode and the body uses instant reflexes for a short time—sometimes just seconds or minutes—and then can start relaxing after the stressor is gone so you can continue on with your day.

Chronic stress, on the other hand, is long term. Dealing with a drawn-out legal issue, for example, or a disease that goes on for months and even years can become a legitimate cause of chronic stress. This type of stress is particularly harmful because it keeps your body and mind on “high alert” all the time without giving it the opportunity to relax and get back to normal functions like resting and digesting.[B]

Stress’s effect on mental health

When you’re feeling stressed you may notice that it affects your mood and attention. You may feel irritable, worried, sad, angry, or otherwise unable to focus in a rational and calm way.[3] [Feel free to add in a story or describe how stress temporarily affects your or your clients’ mood.] Stress can also lead to more serious mental health issues like depression or anxiety.[2,3,4]

Stress’s effect on physical health

Over time, your natural physical reactions to stressors can become chronic and can impact many of your body’s systems and healthy functions. Stress can negatively affect your digestion, immune, cardiovascular and reproductive systems.[1,2,4] This can lead to many symptoms such as digestive distress, headaches, muscle tension, impaired sleep, or weight gain or loss.[1,2,3,4] Stress can also increase your risk for conditions such as asthma, obesity, heart disease, and high blood pressure.[3,5,6]

Stress’s effect on histamine levels

Stress can significantly impact histamine intolerance symptoms by triggering the release of more histamine in the body. When you’re stressed, your body releases cortisol, which can initially help reduce inflammation. However, chronic stress can deplete cortisol levels, leading to an increase in histamine production and an exacerbation of histamine intolerance symptoms. Additionally, stress can negatively affect gut health, where a significant amount of histamine regulation occurs, further worsening the condition.

That’s what we call the histamine-stress cycle. It can be hard to break free from, because our symptoms cause stress and stress exacerbates symptoms. When it comes to histamine and mast cell conditions, stress management can be just as important as what you are eating.

You can see that stress can have so many different and seemingly unrelated health effects. Stress can impact your mental and physical health in a multitude of ways. In the next part, we’ll talk about how these effects are even possible—which becomes clear when you understand the biology of stress.

Your biological responses to stress-The science of stress

Stress starts in the brain. The Mayo Clinic refers to stress as a “complex natural alarm system.”[7] At the base of the brain, there is a small part called the hypothalamus. When triggered by stress, the hypothalamus sets off a cascade of reactions through two different systems: your nervous system and your hormonal system.[7] By understanding these mechanisms, it will become clear how your body physically and mentally reacts to stress with so many possible symptoms and why this increases your risks for many health conditions and diseases.

Stress makes your nervous system more alert and ready to fight, flee, or freeze. One way it does this is by redistributing your body’s resources away from non-essential functions by hyper activating the sympathetic part of your autonomic nervous system.[5,8] This means that it tells the nerves that control your attention, heart rate, blood pressure, breathing, and muscles to ramp up, while at the same time, telling the nerves that control your digestion, immune response, and reproduction that they’re not really needed as much in this stressful moment, so they can ramp down for a while.

When it comes to the hormonal response to stress, this happens via the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA-axis).[5,9,10] One of the major messages from your brain’s hypothalamus goes to your adrenal glands, located on top of your kidneys.[7,10] These glands produce the powerful stress hormones cortisol and adrenaline (also known as epinephrine). These two hormones direct your body to hold off on any resting, digesting, immunity, or reproduction because they’ve been told that your body’s focus and resources need to go toward survival.[7]

These stress reactions happen because your brain and muscles are getting prepared for moving quickly and powerfully. Your heart rate, blood pressure, and breathing increase to supply your brain and muscles with more oxygen.[5,7] Your blood sugar level increases to supply them with fuel.[7]

PRO TIP: Remember your stress reactions are biologically the same whether it’s to literally save your life or if your stress is due to a triggering, annoying, or frustrating situation. That’s not your fault. That’s biology. So, whether you are being chased by a lion, or late for an important meeting, your body’s response triggers a cascade of events in an attempt to keep you “safe.”

When you’re stressed, you may have less control over food cravings[1] .[11] An interesting recent finding is that ghrelin[2] —the “hunger” hormone—is also activated in response to stress.[6] Studies show that, upon acute stress, high levels of ghrelin are immediately released by the stomach into the bloodstream to promote food-seeking and meal initiation. It’s possible that by releasing ghrelin when stressed, the eating that follows helps people alleviate some of their stress. When stress subsides, the levels of ghrelin decrease slowly over the course of minutes or hours, even if nothing is eaten.

Interestingly, the ghrelin response seems to be higher and last longer for people who have excess weight or obesity.[6] Researchers believe that ghrelin’s role in promoting eating during stressful times may be one of the reasons why stress is linked to obesity and difficulty in losing weight. As of now, it is not known which comes first: a higher ghrelin response to stress which contributes to the development of obesity or whether people with obesity develop a heightened ghrelin response as a result of weight gain. More research will likely sort this out in the future.[6]

As you can imagine, once the stressful situation has passed, all of these stress hormones slowly drop down to normal levels and your body can start going back to its balanced state. Your heart rate, blood pressure, breathing, and blood sugar all reduce, and your body can start picking up where it left off in terms of resting, digestion, immunity, and reproduction.[7]

The difference between acute (short-term) stress and chronic (long-term) stress is that with chronic stress, you constantly feel demands and threats over the long run, so this biological reaction continues. This is where long-term consequences such as increased risks for anxiety, depression, digestive issues, headaches, muscle tension, heart disease risk, sleep problems, and weight issues may come into play.[7]

With all of these biological responses, our nervous system and hormones focus on ensuring your body’s resources are focused on survival in this immediate present danger, even if the stressor isn’t, in fact, immediately a matter of life or death. This explains how stress can have such a vast array of seemingly unrelated symptoms: digestive distress, headaches, muscle tension, susceptibility to infections, mood changes, etc., and how living in this stressful state too often for too long can lead to more serious issues mentioned above.

Summary about stress

Stress is a completely normal physical and mental reaction to life’s demands. Stress is not all bad—it can help you reach your goals or literally save your life. The problem is chronic stress because your body responds to all stress in the same BIG way by instantly prioritizing survival mechanisms of fighting, fleeing, or freezing. This means it increases your alertness, blood pressure, blood sugar, and breathing. It also means that it de-prioritizes your ability to rest, digest, fight infections, and reproduce. When stress goes on for a long time and your body and mind don’t get a chance to re-balance, that’s when it can have detrimental effects on your mental and physical health.

Managing stress can be a challenge, but there are many things you can do to try to mitigate the stressor itself. And there are also effective ways to cope and manage your reaction to these stressors in a healthy way. In the next part, I will share some of the common—and uncommon—strategies to help you better manage your stress and reduce those stressors in a healthy and productive way.

The late Beth O’Hara from Mastcell360 has a great write up about the importance of regulating your nervous system HERE.

References

- 1 – Canadian Mental Health Association. (2016, February 28). Stress. https://cmha.ca/brochure/stress/

- 2 – National Institute of Mental Health. (n.d.). 5 things you should know about stress. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/stress

- 3 – US Department of Health and Human Services Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (2021, June 10). Manage stress. My healthfinder. https://health.gov/myhealthfinder/topics/health-conditions/heart-health/manage-stress

- 4 – National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. (2020, January). Stress. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/stress

- 5 – Conversano, C., Orrù, G., Pozza, A., Miccoli, M., Ciacchini, R., Marchi, L., & Gemignani, A. (2021). Is Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Effective for People with Hypertension? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 30 Years of Evidence. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(6), 2882. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18062882

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8000213

- 6 – Bouillon-Minois, J. B., Trousselard, M., Thivel, D., Gordon, B. A., Schmidt, J., Moustafa, F., Oris, C., & Dutheil, F. (2021). Ghrelin as a Biomarker of Stress: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients, 13(3), 784. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13030784

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7997253

- 7 – Mayo Clinic. (2021, July 8). Stress management. https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/stress-management/in-depth/stress/art-20046037?p=1

- 8 – Scholarpedia. (2013, August 17). Nervous system. http://www.scholarpedia.org/article/Nervous_system#:~:text=The%20nervous%20system%20is%20the,the%20brain%20and%20spinal%20cord

- 9 – Heaney J. (2013) Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis. In: Gellman M.D., Turner J.R. (eds) Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1005-9_460

- https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007%2F978-1-4419-1005-9_460

- 10 – Welt, C. (2019, April 30). Hypothalamic-pituitary axis. Up To Date. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/hypothalamic-pituitary-axis

- 11 – Bhutani, S., vanDellen, M. R., & Cooper, J. A. (2021). Longitudinal Weight Gain and Related Risk Behaviors during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Adults in the US. Nutrients, 13(2), 671. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13020671

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7922943

- 12 – Roos, L. E., Cameron, E. E., & Mota, N. (2020, December 15). Beyond self-care: Try these 5 therapeutic tools to manage stress better during COVID-19 restrictions. The Conversation.

- https://theconversation.com/beyond-self-care-try-these-5-therapeutic-tools-to-manage-stress-better-during-covid-19-restrictions-150838

- 13 – Worthen M. & Cash E. (2020, August 29). Stress Management. StatPearls Publishing. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513300/

- 14 – Zhang, J. Y., Cui, Y. X., Zhou, Y. Q., & Li, Y. L. (2019). Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on prenatal stress, anxiety and depression. Psychology, health & medicine, 24(1), 51–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2018.1468028

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29695175

- 15 – Bemanian, M., Mæland, S., Blomhoff, R., Rabben, Å. K., Arnesen, E. K., Skogen, J. C., & Fadnes, L. T. (2020). Emotional Eating in Relation to Worries and Psychological Distress Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Population-Based Survey on Adults in Norway. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(1), 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010130

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7795972

- 16 – Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. (n.d.). 24-hour movement guidelines for adults.

- 17 – Fletcher, B. D., Flett, J., Wickham, S. R., Pullar, J. M., Vissers, M., & Conner, T. S. (2021). Initial Evidence of Variation by Ethnicity in the Relationship between Vitamin C Status and Mental States in Young Adults. Nutrients, 13(3), 792. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13030792

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7997165

- 18 – Public Health Agency of Canada. (2018, October 12). Cannabis and your health: 10 ways to reduce risks when using. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/drugs-health-products/cannabis-10-ways-reduce-risks.html

- 19 – Aeon, B., Faber, A., & Panaccio, A. (2021). Does time management work? A meta-analysis. PloS one, 16(1), e0245066. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245066

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7799745